Physic Nut (Jatropha curcas) – Comprehensive Report

Botanical Description

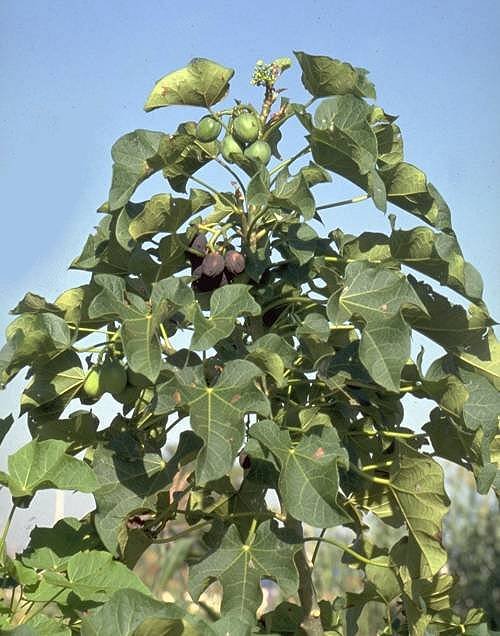

A Jatropha curcas shrub with green fruits on its branches. The Physic Nut (Jatropha curcas L.) is a member of the spurge family (Euphorbiaceae), and it is a semi-evergreen shrub or small tree typically growing up to 6 meters (20 feet) tallen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. It has a slender gray trunk with spreading branches and exudes a milky latex sap when cut. The leaves are green to pale green, arranged alternately (sometimes sub-opposite), and usually three- to five-lobed, with a somewhat palmate appearanceen.wikipedia.org. Small yellowish-green flowers are produced in clusters; the plant is monoecious, bearing both male and female flowers on the same inflorescencepfaf.org. Fertilized flowers develop into oval fruits (capsules) about 2–4 cm, which turn yellow upon ripening and later dry into a dark brown huskpfaf.org. Each fruit typically contains 2–3 black oval seeds resembling castor beans in shape.

Originally native to the tropical Americas (from Mexico and the Caribbean to Central and South America), J. curcas has been spread by humans to tropical and subtropical regions worldwideen.wikipedia.org. It thrives in semi-arid climates – the plant is highly drought-tolerant and can survive on as little as 250 mm of rainfall per yearen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Physic nut is often found in savannahs, open woodlands, and scrublands, and it tolerates poor, stony soils where few other plants thrivepfaf.org. It grows well on gravelly, sandy, and even saline soils, provided they are well-drainedpfaf.org. However, the plant is frost-tender and cannot withstand cold climates. Because it is unpalatable to livestock (due to its toxicity), Jatropha is commonly used as a living fence or hedge around fields and homesteads in the tropics. Its fast growth and deep root system also make it useful for erosion control on degraded landspfaf.org. Common English names for J. curcas include physic nut, Barbados nut, purging nut, and poison nut, reflecting its medicinal history as well as its toxic natureen.wikipedia.org.

Medicinal Uses and Home Remedies

*(Safety Note: Extreme caution is advised in using J. curcas medicinally, as all parts of the plant are poisonous if ingestedpfaf.org.) The Physic Nut has a long history of use in traditional medicine across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Almost every part of the plant has been utilized in folk remedies, usually for external applications or carefully controlled doses, owing to its potent bioactive compounds. Below is an overview of traditional medicinal uses and home remedies associated with Jatropha curcas:

Latex/Sap: The milky white latex from the stem and leaves is applied externally as a disinfectant and styptic (to stop bleeding). It exhibits antibiotic activity against bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli, and it helps coagulate blood, which explains its use on cuts, wounds, and mouth ulcerspfaf.orgtropical.theferns.info. For example, a drop of latex might be used on fresh wounds or bleeding gums to promote clotting and prevent infection (in some places, it’s used as a quick remedy for bleeding tooth sockets or gum sores)pfaf.org. In children, diluted latex has been used traditionally to treat mouth infections (such as thrush) due to these antimicrobial propertiespubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. (Note: The latex can irritate skin, so it must be used in very small quantities.)

Bark and Roots: The juice of the bark is used in West African and Asian folk medicine to treat malarial fevers and reduce inflammatory swellingpfaf.org. Externally, bark sap is applied to skin problems; for instance, it can be dabbed on burns, scabies, eczema, or ringworm lesions to aid healingpfaf.org. A paste of the bark is applied to the gums to relieve gum inflammation, sores, and toothachepfaf.org. In Nepal, small fresh bark pieces are even chewed or kept in the mouth for an hour to treat pyorrhea (periodontal disease) and mouth infectionstropical.theferns.infotropical.theferns.info. The root bark is also recorded in folk remedies for dysentery and jaundice, often ground into a preparation given in very small dosespfaf.org. Additionally, the dried roots have been used in some cultures as part of an antidote for snakebite (although effectiveness is anecdotal)pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Leaves: The leaves of J. curcas are applied both internally (as teas) and externally. A leaf infusion or decoction is taken to alleviate coughs, colds, and fever, and it is sometimes used as a diuretictropical.theferns.infotropical.theferns.info. In traditional African medicine, steaming or stewed leaves are given for jaundice and to reduce fevertropical.theferns.info. Leaf preparations are also used to treat malaria symptoms, and a warm poultice of Jatropha leaves is placed on swollen joints or rheumatic pains for reliefpfaf.org. Some cultures apply crushed leaves to skin sores, boils, and guinea worm ulcers to help them healpfaf.org. An enema of leaf extract was used historically in treating convulsions or fits in children (though this practice is now rare)tropical.theferns.info. In Ghana, the ashes of burnt Jatropha leaves are mixed in water and applied rectally to treat hemorrhoids, highlighting the plant’s anti-inflammatory and astringent propertiestropical.theferns.info.

Twigs: The slender young twigs serve as natural chewing sticks (toothbrushes) in rural communities (for example, in Nepal and India). Chewing on a Jatropha twig releases its sap, which is believed to strengthen the teeth and gums, treat toothache, and curb gum bleedingpfaf.orgtropical.theferns.info. This practice also has an antiseptic effect in the mouth. The twigs are considered especially good for treating bleeding or swollen gums, owing to the styptic quality of the latex withintropical.theferns.infotropical.theferns.info.

Seeds: The seeds of the physic nut are notoriously purgative. In traditional usage, they were taken in very small quantities as a strong laxative or emetic to treat constipation and intestinal parasites. Typically, 1–2 roasted seeds were ingested to induce purging (as reported in folk medicine from Gabon and other parts of Africa)tropical.theferns.info. The seeds have a pleasant nutty taste (often compared to beechnuts), which belies their potencypfaf.org. If eaten beyond a small dose, they cause severe griping, vomiting, and diarrhea within about 30 minutestropical.theferns.info. In fact, as few as 3–5 raw seeds can poison a person, so traditional healers exercised great caution. Due to their cathartic effect, the seeds earned the name “purging nut” and have even been used as a drastic remedy for severe constipation or to expel intestinal worms (though safer alternatives are preferred today). There are also reports of the seeds being used in the treatment of syphilis in folk practice, likely as part of a purgative regimentropical.theferns.infotropical.theferns.info. Important: In modern times, consuming Jatropha seeds is strongly discouraged due to the risk of poisoning.

Seed Oil: Oil extracted from Jatropha seeds (often called “curcas oil”) is a traditional remedy for various skin and joint ailments. The oil is applied topically to treat skin diseases such as eczema, ringworm, dermatitis, and minor sorespfaf.orgpfaf.org. It is also commonly used as a massage liniment for rheumatism and arthritis, as it creates a warming, counterirritant effect that can soothe painpfaf.orgpfaf.org. In parts of West Africa, the oil is an ingredient in an herbal rub (known in Hausa as “kufi”) for alleviating rheumatic pains and parasitic skin conditionspfaf.org. Additionally, Jatropha oil is believed to stimulate hair growth; it is sometimes applied to the scalp or used in hair oils to address baldness or scalp infections (similar to castor oil’s traditional use)pfaf.org. Internally, however, Jatropha oil is highly purgative and toxic – it was used historically as a drastic purgative (much stronger than castor oil), but ingesting it is dangerous and is no longer recommendedtropical.theferns.infotropical.theferns.info.

In summary, Jatropha curcas is valued in ethnomedicine for its antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, and laxative properties. Many of its traditional uses (e.g. as an antibiotic agent, or anti-parasitic) have been supported by modern research showing that Jatropha contains compounds with biological activity (e.g. phorbol esters, curcin, saponins)pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Nevertheless, extreme care must be taken with home remedies: treatments are usually external or involve tiny doses, because all parts of the plant are toxic. It is always advisable to consult an expert herbalist or healthcare provider before using physic nut for any medicinal purpose.

Nutritional Value

Jatropha curcas is not ordinarily used as a food plant due to its toxicity. However, understanding its nutritional makeup is important in contexts like famine use, animal feed (after detoxification), or for its by-products. The seeds are rich in oil and protein, albeit accompanied by anti-nutrients and toxins. On average, Jatropha seeds contain about 27–40% oil by weighten.wikipedia.org. This oil is composed largely of unsaturated fatty acids (around 80% unsaturated, predominantly oleic and linoleic acids) and about 20% saturated fatsen.wikipedia.org. The presence of these oils is what makes Jatropha a candidate for biofuel production rather than human consumption. In addition to fats, the seeds also have significant protein content (the seed meal after oil extraction can have over 50% crude protein) and some carbohydrates. Notably, analyses have found various sugars in the seeds (saccharose, raffinose, stachyose, glucose, fructose, galactose) as well as proteins, although these nutrients are locked behind the plant’s toxic factorsen.wikipedia.org.

Despite its inherent toxicity, certain parts of Jatropha are occasionally used as emergency or traditional foods after careful preparation. For instance, the tender young shoots and young leaves are reported to be edible when properly cooked (steamed or boiled) to neutralize toxinspfaf.org. In some cultures, steamed Jatropha leaves are eaten as a green vegetable (much like spinach or other leafy greens) and are valued for their minerals and fiber, though this is done sparingly and with cautionpfaf.org. The cooking process greatly reduces the phorbol ester content, making the young leaves safer to consume – they are described as safe to eat once steamed or stewed, as any bitterness and some toxins are leached outpfaf.org. Similarly, in certain regions of Mexico (Veracruz and others), local non-toxic varieties of Jatropha (known as piñón manso, etc.) have traditionally been consumed: roasted Jatropha seeds of these varieties are eaten in small quantities, having a pleasant nutty flavor akin to beechnutspfaf.orgen.wikipedia.org. These Mexican varieties have been naturally selected to have much lower levels of toxic phorbol esters (about 0.27 mg/g vs. 5–6 mg/g in toxic varieties)mdpi.com, making them edible when prepared. However, even “edible” Jatropha seeds are consumed cautiously – typically just a few seeds – to avoid any purgative effectstropical.theferns.info.

Apart from potential human consumption, the nutrient content of Jatropha is significant for agricultural uses. The press cake (residue after oil extraction from seeds) is rich in nitrogen (around 2.5–3% N), potassium (~3% K), and moderate phosphorus (~0.2% P), along with micronutrientsresearchgate.netresearchgate.net. This makes it a potent organic fertilizer or soil amendment (after proper detoxification or composting to degrade toxins)researchgate.netresearchgate.net. In fact, the seed cake’s high protein content suggests it could be used as animal feed if the toxic compounds (curcin and phorbol esters) are removed – research is ongoing into detoxification methods to safely use Jatropha seed cake as a protein-rich feed supplementen.wikipedia.org. Until such methods are perfected, the primary “nutritional” uses of Jatropha remain indirect (biofuel and fertilizer) rather than as a food source. In summary, while J. curcas contains substantial oils, proteins, and minerals, its value to nutrition is only realized when its toxic elements are eliminated. For everyday purposes, it is not a dietary plant – any traditional edible use is limited, cautiously practiced, and typically involves special non-toxic strains or thorough processingen.wikipedia.orgpfaf.org.

Toxicity and Safety Information

⚠️ Warning: All parts of the Physic Nut plant are poisonous to humans and animals if ingested. The plant earned names like “poison nut” for good reason – it contains several toxic compounds that can cause serious illness. Every part of Jatropha curcas (leaves, seeds, bark, latex, etc.) is highly purgative and poisonous when consumedpfaf.org. The primary toxins identified are phorbol esters (potent irritants) and curcin, a toxic protein (toxalbumin) similar to ricin in castor beansen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. The oil from the seeds is especially rich in a toxin called curcasin, and the seed cake contains curcin and related lectins that can be deadlypfaf.org. Even the vegetative parts have irritant chemicals: for example, a resin in the seeds and sap can cause intense skin inflammation, redness, and blistering on contactpfaf.org. Given these constituents, ingesting Jatropha causes violent reactions – the plant is effectively a strong poison.

Toxic effects: If someone eats physic nut seeds or parts of the plant, symptoms usually start with a bitter, acrid taste followed by a burning sensation in the throat. Within 15–30 minutes, severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea occurtropical.theferns.info. The purging can be so intense that it leads to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and shock if not treated. Reports indicate that as few as 3 seeds can induce these symptoms in a child, and around 5–8 seeds (or roughly 0.1–0.3 mg of curcin per kg body weight) could be lethal for a childtropical.theferns.info. Adults might tolerate slightly more, but cases of poisoning (sometimes fatal) have been documented from ingesting Jatropha seeds or oil. In addition, skin or eye exposure to the sap/latex can cause irritation: direct contact may lead to dermatitis with redness and blister formation, and if the latex gets in the eyes it can cause intense burning and inflammation. The toxic phorbol esters are both a skin irritant and tumor-promoter, which is why raw Jatropha is absolutely not for casual useen.wikipedia.org. The plant’s toxicity is so pronounced that Jatropha was traditionally used as a fish poison (stunning or killing fish when thrown in ponds) and as an ordeal poison in certain culturespfaf.orgplantsandculture.org. Livestock generally avoid browsing it, but if hungry animals consume Jatropha leaves or seeds, they can suffer similarly severe gastric distress or even die. There is currently no specific antidote to Jatropha poisoning; treatment is supportive (rehydration, activated charcoal, etc.), so prevention is key.

Safe usage and limits: Jatropha curcas should never be eaten raw. Any internal medicinal use of Jatropha must be approached with extreme care (and is not recommended outside of professional herbal practice). Traditional healers who employed Jatropha always did so in tiny doses and often after special preparation (like roasting seeds, fermenting, or heavy dilution), fully aware of its dangerstropical.theferns.info. For example, taking more than 1–2 prepared seeds was known to be dangeroustropical.theferns.info. Modern herbal medicine generally discourages internal use of Jatropha because the margin between “therapeutic” and toxic dose is too narrow. Children are particularly vulnerable and should never be given any Jatropha remedy. If using the plant externally, avoid applying the fresh latex to large skin areas or sensitive skin – even external use can cause blistering in some peoplepfaf.org. Always wash hands after handling Jatropha plant parts, and keep livestock and pets away from it.

One positive note is that there are naturally non-toxic varieties of J. curcas (notably in Mexico), which lack phorbol estersen.wikipedia.org. These have been used for human consumption (roasted seeds, etc.) without ill effect in local communitiesen.wikipedia.orgmdpi.com. However, these varieties are not widespread. Unless you are certain you have a non-toxic strain (and even then, it’s wise to be cautious), assume any Jatropha plant is poisonous. In summary, the safety rule for physic nut is: external medicinal use only, and even then with care – and do not ingest unless under expert guidance. All individuals should be aware of its toxicity, especially in areas where the plant grows commonly, to prevent accidental poisonings.

Agricultural and Industrial Uses

Beyond its medicinal folklore, Jatropha curcas has gained fame for a range of agricultural and industrial applications. Its hardy nature and chemical makeup make it valuable in sustainable farming systems, renewable energy, and other industries:

Biofuel (Biodiesel) Production: Perhaps the most publicized use of Jatropha is as a source of biofuel. The seeds contain a high percentage of non-edible oil (typically 30–40%) which can be extracted and processed into biodieselen.wikipedia.org. Jatropha oil can be converted via transesterification into a high-quality biodiesel that burns in standard diesel enginesen.wikipedia.org. This biodiesel has similar performance to conventional diesel and has been touted as a renewable, cleaner alternative. Plantations of Jatropha have been established in parts of Asia, Africa, and India with the aim of producing biofuel on marginal lands. In addition, Jatropha oil has been explored for biokerosene and for use in thermal energy storage fluidsen.wikipedia.org. A benefit of Jatropha as a biofuel crop is that it can grow on poor soils with little water, so it doesn’t necessarily compete with food crops for prime farmland (though yields are higher on better soil and rainfall). While early “green energy” enthusiasm around Jatropha has tempered (due to challenges in cultivation and lower-than-expected yields in marginal conditions), it remains a promising feedstock for biodiesel, especially as agronomic improvements continue.

Living Fence and Pest Barrier: Jatropha is widely planted as a living fence around fields and gardens. The reasons are twofold: first, its toxicity means livestock or wild animals will not eat it, so a dense hedge of Jatropha can effectively keep cattle, goats, or pests out of a crop fielden.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Second, the shrub’s thick leafy growth and year-round presence (in warm climates) form a physical barrier. Farmers appreciate that a Jatropha hedge is low-maintenance (it regenerates even if cut) and can last for decades. The plant’s pesticidal properties also contribute – traditionally, people believe that having Jatropha around discourages certain insects and even snakes (as mentioned in cultural uses). In some regions, dried Jatropha leaves or branches are also stored with grains to repel storage pests.

Natural Insecticide and Pest Control: Research has confirmed that J. curcas contains compounds with insecticidal and repellent activity. Extracts from Jatropha (such as seed oil, leaf extracts, or seed cake extracts) have been successfully used to control a variety of agricultural pests. For example, studies show Jatropha’s botanical extracts can kill or deter insects like grain storage weevils, aphids on crops like cabbage and sorghum, fruit flies, and even locustsmdpi.commdpi.com. These extracts caused high insect mortality, reduced egg-laying, and lowered feeding damage in trialsmdpi.com. The active components (e.g. phorbol esters, saponins, curcin) act as natural pesticides that are biodegradable. Farmers and researchers are interested in Jatropha-based insecticides as an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic chemicalsmdpi.commdpi.com. For instance, simple cold-pressed Jatropha seed oil can be sprayed to control pests; it works as a contact poison and antifeedant. Similarly, Jatropha seed cake (after oil extraction) has shown potential as a bio-insecticide and even nematicide when applied to soilsjournalcra.com. However, care must be taken since these natural pesticides are broad-spectrum and also toxic to non-target organisms if misused.

Soil Improvement and Erosion Control: Jatropha’s ability to grow in poor soils and its deep root system make it useful for land rehabilitation. It is often planted on eroded hillsides or wastelands to stabilize the soil and reclaim fertility. The roots help prevent soil erosion by holding topsoil in placepfaf.org. The plant also adds organic matter: its fallen leaves and fruit husks decompose to return nutrients to the ground. Additionally, Jatropha can be intercropped in agroforestry systems as a shade plant or windbreak, protecting more delicate crops. In areas prone to desertification, lines of Jatropha shrubs have been used as a “green belt” to break wind and slow land degradation. Moreover, the press cake from seed processing is rich in nutrients and can be used as an organic fertilizer or soil amendment. When Jatropha seed cake is applied to fields (after detoxification/composting), it significantly increases soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium levels and boosts soil microbial activityresearchgate.netresearchgate.net. Studies have shown that incorporating Jatropha seed cake improves soil health parameters – increasing organic carbon, reducing bulk density, and enhancing water retention in sandy or depleted soilsresearchgate.netresearchgate.net. This contributes to sustainable agriculture by recycling the plant’s biomass back into the soil.

Industrial Products (Soap, Fuel, etc.): The non-edible Jatropha oil has various industrial uses besides biodiesel. One traditional use is soap-making: Jatropha oil saponifies readily and has been used to create soap that is reported to be effective against skin ailments (in rural areas, homemade Jatropha soap is used for treating fungal infections and itchy skin)pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. The soap has good cleansing properties and the added benefit of the oil’s antimicrobial traits. Jatropha oil also burns with a clear flame, so it has been used as a lamp oil in lamps or lanterns in remote areas (similar to coconut or kerosene lamps). The oil’s high flash point and slow burning make it a relatively safe fuel for household lighting or even cooking (in specially designed stoves). Another application is in the manufacture of candles and cosmetics – after refining, Jatropha oil can be an ingredient in detergents or skincare products (though any toxins must be removed for cosmetics). The seed cake, aside from fertilizer use, has been explored as a source for biogas production via anaerobic digestion, utilizing its organic content to generate methane. Finally, because Jatropha contains potent chemicals, there is research into developing pharmaceutical or biocidal products from it – for example, using its curcin in bio-pesticides or its latex compounds in wound-healing formulations. These uses are still experimental but illustrate the wide-ranging potential of the plant.

In essence, Jatropha curcas is a “multipurpose” crop. It can help improve farming sustainability – by acting as a natural fence, a pest control agent, and soil improver – and at the same time serve as a source of renewable energy and raw materials for cottage industries. The plant’s ability to grow on marginal land with minimal inputs further enhances its appeal for rural development and agroforestry projects. However, harnessing its benefits requires careful management of its toxic aspects to ensure safety for people and livestock.

Cultural and Ethnobotanical Significance

Throughout the tropics, the physic nut tree has woven itself into local cultures, folklore, and spiritual practices. Its prominence in ethnobotany goes beyond practical uses, touching on beliefs and traditions:

Protective and Spiritual Roles: In many African and Caribbean communities, Jatropha curcas is regarded as a powerful protective charm. For example, in Zimbabwe, people traditionally plant Jatropha shrubs around their homesteads to ward off snakes and evil spiritsplantsandculture.org. The plant is thought to form a spiritual barrier; its presence is believed to keep witches or malevolent forces from entering the home. This belief is echoed in the Caribbean—Trinidad and Tobago folklore holds that a physic nut tree at the corners of one’s property will deter evil entities like the soucouyant (a witch or vampire in local legend) from crossing into the yardplantsandculture.org. Similarly, in rural Jamaica, farmers would secretly bury a Jatropha nut or branch in their field as a talisman to guard against the “evil eye” – the envy of neighbors which could otherwise blight their cropsplantsandculture.org. The plant’s human-like sap (it “bleeds” red sap and “milks” white latex) may have contributed to mystical associations, as it seemed to possess a lifeblood and milk of its ownplantsandculture.orgplantsandculture.org. Some also say the unpleasant taste and toxicity of the plant “repels” evil, a symbolic parallel to repelling physical pests.

Ordeal and Oath Rituals: Jatropha curcas has even been used in traditional justice rituals. An example comes from Zimbabwean custom, where a concoction made from Jatropha (often the toxic seeds or leaves) is given to an accused person in a trial-by-ordeal. It’s said that if the person swallows the brew and does not vomit it back up, they are deemed guilty – the logic being that the spiritually “impure” will be unable to expel the impurity they’ve ingestedplantsandculture.org. (In reality, given Jatropha’s emetic power, almost everyone vomits, so the ordeal is heavily stacked in favor of proving innocence by purging.) Such practices highlight the reverence and fear the plant inspired; it was quite literally used as a tool for divine judgment in community disputes.

Religious Festivals and Symbolism: In parts of Central America and the Caribbean, Jatropha curcas became entwined with Christian religious symbolism, particularly following Spanish colonization. A notable tradition occurs on Good Friday (during Easter): people will cut or pierce the trunk of a Jatropha tree, causing its dark red sap to flow, which is seen as a representation of the blood of Christ at the Crucifixionplantsandculture.org. This custom, observed in countries like Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Haiti, is a fusion of indigenous plant lore with Catholic faith – the physic nut tree stands as a living symbol of the suffering and resurrection themes of Easter. The day the tree “bleeds” is Good Friday, and by Easter Sunday the sap has coagulated, which some interpret as the tree “healing” in time for the celebration of resurrection. Such practices have kept Jatropha in the cultural consciousness as more than just a plant – it becomes a participant in sacred time.

Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Folklore: Across its native and introduced range, Jatropha has picked up many local names and folk sayings. In parts of Mexico, it’s called “piñón de tempate” or “piñón manso”, and was long used by indigenous groups for its medicinal oil and as a dye (its bark and roots yield a tannin used for tanning leather). In India, villagers historically used the plant for oil lamps and referred to it as “Bagbherenda” (wild castor) – tying it to castor oil plant in folklore. Various superstitions exist, such as the idea that planting a Jatropha on a grave would prevent the spirit from roaming (as noted in some African cultures), or conversely that a flourishing Jatropha tree near a home brings good fortune and health. The durable nature of the plant, which can live ~40-50 years, also made it a symbol of resilience and endurance in the face of drought, so songs or proverbs sometimes invoke the physic nut in the context of survival.

Colonial and Economic History: Jatropha curcas was one of the plants distributed by European colonizers in the tropics due to its utility. Portuguese traders are credited with spreading it from the Americas to Africa and Asia in the 16th century, using it as living fencing around plantations and as a source of lamp oilen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. It thus became part of the colonial agrarian landscape, often planted around indigo, coffee, or sugar estates. Locally, people integrated it, calling it by names in their own languages and incorporating it into traditional medicine and craft. For instance, in parts of West Africa, the seeds were strung into necklaces for fetish priests (likely because of their supposed protective powers), and in Southeast Asia, the latex was used to mark tribal tattoos. Over time, the plant’s roles expanded from the practical to the cultural.

In conclusion, Jatropha curcas holds a fascinating place in ethnobotany – medicinal “physic,” protective charm, spiritual symbol, and economic resource all at once. Its use in wards against evil and in sacred rituals underscores how a plant’s utility and peculiar traits (like bleeding sap or toxicity) can elevate it into myth and ceremony. Even as modern science examines Jatropha for biodiesel or pharmaceuticals, local cultural knowledge remembers it as the tree that can protect a home’s four corners, test a person’s innocence, and bleed on Good Friday, connecting the natural world to the spiritual in everyday lifeplantsandculture.orgplantsandculture.org.

Sources: The information in this report is drawn from a variety of trusted sources, including ethnobotanical databases, scientific reviews, and field studies on Jatropha curcas. Key references include the Plants For A Future databasepfaf.orgpfaf.org, which provides details on traditional uses and toxicity; academic journals exploring Jatropha’s biofuel potential and pest control propertiesen.wikipedia.orgmdpi.com; and cultural research documenting the plant’s role in folklore and traditionsplantsandculture.orgplantsandculture.org. These sources have been cited throughout the text for verification of facts. The report emphasizes accurate, up-to-date information (as of 2025) and highlights safety considerations due to the plant’s poisonous nature.

🌿 Explore More Natural Remedies

Click here to read more articles